לעבעדיקע שמועסן שבת נאָכן טשאָלנט

Shabbos Afternoon: Lively Debates About the Forverts Articles

פֿון דזשעראָם קאָוואַלסקי (ניו־יאָרק, נ״י)

Scroll down for English

(דאָס איז טייל פֿון אַ סעריע פֿאָרווערטס־זכרונות פֿון אונדזערע לייענער, וואָס זענען אָפּגעדרוקט געוואָרן אינעם סאַמע לעצטן געדרוקטן נומער, אַפּריל 2019)

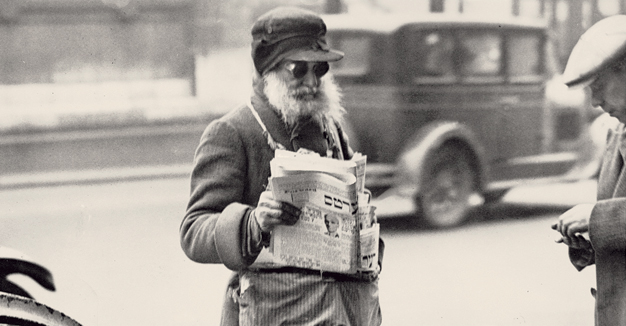

דער פֿאָרווערטס איז געווען אַ וויכטיקער טייל פֿון מײַן טאַטנס טאָגטעגלעכן לעבן. ווי אַלע מאַנסבילן אין זײַנע יאָרן, פֿלעג ער צונויפֿלייגן די צײַטונג און אַרײַנלייגן אין דער דרויסנדיקער קעשענע פֿון זײַן רעקל און זי אַזוי אַרומטראָגן אַ גאַנצן טאָג. במשך פֿונעם טאָג פֿלעג ער אים אַרויסנעמען, איבערלייענען אַן אַרטיקל אָדער צוויי, דערנאָך ווידער צונויפֿלייגן די צײַטונג — און צוריק אַרײַן אין קעשענע. אַזוי האָט ער געטאָן יעדן טאָג. געלייענט יעדן אַרטיקל, אַרײַנגערעכנט די שיינע ראָמאַנען.

יעדן שבת נאָך מיטאָג האָט ער מיט זײַנע פֿרײַנד זיך פֿאַרזאַמלט בײַ אונדז אין שטוב איבער טיי און לעקעך, און מיט התלהבֿות זיך אויסגעטענהט שעהען לאַנג וועגן די אַרטיקלען וואָס זיי האָבן געלייענט אין פֿאָרווערטס. כּדי צו פֿאַרשטאַרקן אַן אַרגומענט האָט יעדער פֿון זיי אַרויסגענומען דעם שײַכותדיקן נומער פֿון דער זײַט־קעשענע פֿון אַנצוג־רעקל (שבת האָט מען זיך דאָך שענער אָנגעטאָן) אַרויסגענומען איינעם פֿון די נומערן פֿון יענער וואָך וואָס ער האָט שוין פֿון פֿריִער געהאַט פּלאַנירט וועגן דעם צו רעדן.

זייערע ווערטער — תּמיד אויף ייִדיש, פֿאַרשטייט זיך — זענען באַגלייט געוואָרן פֿון געוויסע זשעסטן וואָס האָבן מיר אויסגעזען זייער ייִדישלעך. אַז מע האָט געקוועטשט מיט די אַקסלען, האָט עס געמיינט: „נו, איז וואָס?‟ אַז מע האָט אויסגעשטרעקט אַ האַנט מיט דער דלאָניע אַראָפּ און מע גיט אַ זעץ אין טיש, הייסט עס: „נאַרישקייטן!‟ אַז מע האָט געפֿאָכעט מיטן אָרעם בעת מע האָט אויסגעדרייט דעם קאָפּ פֿונעם „קאָנקורענט‟ אינעם וויכּוח האָט עס געהייסן: „דו ווייסט בכלל נישט וואָס דו רעדסט!‟ מײַן באַליבטסטער זשעסט איז געווען ווען מע האָט אײַנגעבעכערט דעם אויער, שרײַענדיק: „הע?‟ וואָס מיינט: „זײַ מיר מוחל, איך בין אַ ביסל טויב, איז מיר שווער צו הערן וואָס דו האָסט געזאָגט. קענסט עס איבערחזרן?‟ (איינער פֿון זיי איז טאַקע געווען טויב ווי די וואַנט…)

כאָטש אַ סך פֿונעם שמועס איז געווען וועגן די נײַעס פֿון טאָג, בפֿרט ידיעות און פּאָליטיק אין שײַכות מיט ישׂראל, האָט מען אויך אַרומגערעדט די בעלעטריסטיק אָפּגעדרוקט אינעם פֿאָרווערטס. זיי האָבן אָפֿט גערעדט וועגן די ברידער זינגער, און האָבן יאָרן לאַנג דעבאַטירט צי באַשעוויס אָדער זײַן פֿאַרשטאָרבענער ברודער, סרוליק, איז געווען דער בעסטער שרײַבער.

דאָס דערמאָנט מיר אין אַ צווייטן סרוליק: מײַן טאַטנס אַ פֿרײַנד — סרוליק האַרצשטאַרק, וואָס איז געווען אַ פֿאַכמאַן פֿון אַ פֿאַרגאַנגענער תּקופֿה: אַ ייִדישער זעצער בײַם פֿאָרווערטס. פֿון צײַט צו צײַט האָט סרוליק אויסגעזאָגט אַז דער פֿאָרווערטס וועט אין גיכן אָנהייבן דרוקן אַ נײַעם, גוט־געשריבענען ראָמאַן. בײַ די מענער און פֿרויען וואָס זענען געזעסן בײַ אונדזער טיש שבת נאָך מיטאָג איז אַזאַ ידיעה געווען נאָך חשובֿער ווי אַ גוטע עצה פֿון אַן אינעווייניקסטן אינוועסטירער בײַ דער בערזע.

Shabbos Afternoon: Lively Debates About the Forverts Articles

Jerome Kowalski, New York, NY

Part of a series of Forverts memories by our readers, published in the very last paper edition of the Forverts, April 2019

It was a newspaper that my father, like all his peers, would fold into fourths and carry all day in the outer pocket of his jacket and then carefully and repeatedly unfold it and read throughout the day. Every day. Every article. Every feature including the great fiction. Then on Shabbos afternoons, he and his friends would gather at our house over tea and cake and passionately argue for hours about every item that appeared during the preceding week. To make their points, the men would often reach into their suit jacket side pockets, where they had previously placed a folded copy of one of the week’s previous editions of the Forverts, having carefully planned to use that particular edition to bolster an argument they had prepared for that week’s gathering.

The raucous arguments, always in Yiddish of course, were often punctuated with hand, shoulder and arm motions which I always thought were uniquely Yiddish. A shoulder shrug meant: “So what?” Extending an arm, palm down and then moving the palm down while looking at your interlocutor meant “nonsense.” Waving the arm sideways, with palm perpendicular to the floor, while looking away from the adversary of the moment meant “you don’t know what you’re talking about.” And my favorite was the hand cupped to the ear and a shouted “heh?”, which meant: “I beg your pardon, but I’m a little hard of hearing. I therefore had great trouble hearing what you just said. Accordingly, would you be kind enough to repeat that one more time, a little louder, please?” (One of them really was hard of hearing.)

While much of the conversation was about the news of the day, with an emphasis on politics and most often about news or politics emanating from Israel, much was also discussed about the fiction appearing in the Forverts. They spoke about the Singer Brothers as if they were intimate friends of theirs. For years, they debated whether Bashevis, as they called him, or his deceased brother, Srulik, was the better writer.

Speaking of people named Srulik, among my father’s larger circle of friends was Srulik Harczstark, who was an artiste of that bygone era. Srulik was a Yiddish linotype setter at the Forverts. From time to time, Srulik would let slip that in short order there would be a new and well-written piece of fiction that would be appearing in the paper. That information was viewed by the men and women gathered around our Shabbos afternoon table as far more valuable than any insider stock market tip.

די לעצטע אַרטיקלען

The Yiddish Daily Forward welcomes reader comments in order to promote thoughtful discussion on issues of importance to the Jewish community. In the interest of maintaining a civil forum, The Yiddish Daily Forwardrequires that all commenters be appropriately respectful toward our writers, other commenters and the subjects of the articles. Vigorous debate and reasoned critique are welcome; name-calling and personal invective are not. While we generally do not seek to edit or actively moderate comments, our spam filter prevents most links and certain key words from being posted and The Yiddish Daily Forward reserves the right to remove comments for any reason.